Pretentious and Elitist About Tastes in Movies Music Art

Peter Bradshaw on fine art movies

This is a red rag to a number of different bulls. Lovers of what are called arthouse movies resent the characterization for beingness derisive and philistine. And those who hate it bristle at the implication that there is no artistry or intelligence in mainstream entertainment.

For many, the stereotypical arthouse film is Ingmar Bergman's The 7th Seal. Sergei Eisenstein's Battleship Potemkin was a classic art picture from the 1920s and Luis Buñuel investigated cinema'due south potential for surreality like no 1 earlier or since. The Italian neorealists applied the severity of art to a representation of society and the French New Wave iconoclastically brought a self-deconstructing disquisitional awareness to motion picture-making. Yasujiro Ozu conveyed a transcendental simplicity in his work. Andrei Tarkovsky and Michelangelo Antonioni achieved a meditative dazzler, while David Lynch and John Cassavetes demonstrated an American reflex to the genre.

Arthouse movie theater is dismissed as the connoisseur's elite fetish; others find it, in the dumbed-down movie house jungle, to exist an endangered species.

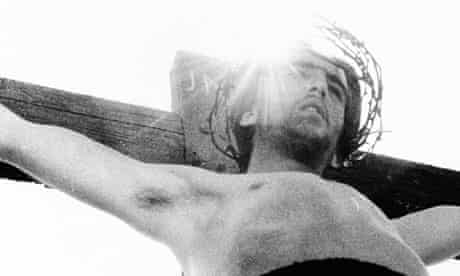

ten. The Gospel According to Saint Matthew

A gay, Marxist Catholic: not the most likely candidate, yous'd accept thought, to make arguably the greatest of all religious films – and one of the very few based on the New Attestation that doesn't lapse into hectoring, literal piety. Pasolini had already roused the wrath of the religious establishment with La Ricotta, a 35-minute one-act on the making of a biblical movie; he actually received a four-month jail judgement equally a result. But the Gospel According to St Matthew is altogether different: serious, spiritual and utterly articulate-eyed about getting to the centre of the Christian gospel. And though Pasolini remained a not-believer, his film was dedicated to "the dearest, happy, familiar retentiveness of Pope John XXIII".

This was Pasolini's third full-length feature, and with it he began his experiments with anthropology that would mark much of his future output. An 60 minutes-long documentary, Location Hunting in Palestine, showed him looking for places to shoot his film; intriguingly, he rejected modern Israel and neighbouring Arab areas for having lost the aboriginal biblical spirit. He ended up doing what you suspect he wanted to do all along: filming in the rundown southern Italian metropolis of Matera.

Pasolini's Gospel is a long way away from the stolid interpretations nosotros've get accustomed to from the Cecil B DeMille school. Everything is simplicity itself: the primitive backdrop, the sparsely sketched-in scenes, the minimal dialogue (practically all lifted from the biblical text itself). Pasolini's aim was to extract the ancient essence from the Jesus story; he does this not by verbal recreation, but by inspecting faces, evoking Renaissance and medieval iconography, and mixing Bach, Mozart, spirituals and African masses on the soundtrack. If ever a moving-picture show told a cute, savage truth, this is it. Andrew Pulver

nine. The White Ribbon

What is information technology about Michael Haneke's 2009 Palme d'Or winner that makes information technology then immaculately disquieting? Information technology's not just the plot: a serial of crimes – some ascribable, well-nigh anonymous – rumple the surface of a small town in northern Germany on the eve of the first world war. A disciplinarian dr. tries and fails to instil a sense of responsibility and culpability into his children. A woman is left by her lover, then subjected to a torrent of abuse that makes Max von Sydow's dismissal of his girlfriend in Ingmar Bergman's Winter Calorie-free (a film whose warm monochrone this movie echoes) look empathetic in comparison.

It'southward clearly – and this is, by and large, a strikingly foggy film – a fascist parable, an attempt at explaining the psychology of the people who came to power some xxx years later. It's likewise a mystery without resolution, a whodunnit with a hole at the centre – which is why it'due south 1 of those films more than satisfying on second view, when yous're primed for the withheld resolution.

But all this is standard-effect for Haneke – not a huge leap on from Hidden or Funny Games. What makes The White Ribbon the finer – and the more than sinister – film are the flickers of warmth and sense of humor. The md'due south young son, traumatised by the decease of his pet caged bird, and, about of all, the unimpeachably sugariness romance between our schoolmaster narrator and a fresh-faced servant girl. The scene in which they get for a picnic and she tearfully requests that they don't go to a spot too remote, is unforgettable, less for the undertone of previous horrors, than the fiance'south baffled acquiescence. When all around you have a heart of coal, kindness tin can be the more upsetting.

Haneke's films always experience, once the credits take rolled, untoppable. This 1 surely is. Catherine Shoard

8. Fanny and Alexander

Ingmar Bergman's cocky-styled farewell to cinema is an opulent family saga, by turns bawdy, stark and strange. For novices who are put off past the managing director'south reputation as a dour, difficult doom master, the picture provides a good introduction. But it may besides count equally the ideal last destination: the picture in which Bergman took hold of his demons and forged a kind of truce.

The plot, in a nutshell, goes like this: two wealthy siblings, Fanny (Pernilla Allwin) and Alexander (Bertil Guve), abound up in the bosom of a lovingly dysfunctional domicile. Following their father's death, their female parent marries the bishop (a superb operation from Jan Malmsjö) and an Oedipal struggle breaks out between Alexander and his icy new stepfather. Matters are resolved in a devastating concluding department within an old marvel shop in which Alexander is shown "the swift way that evil thoughts can go".

Forth the way nosotros run across an androgynous madman, a swollen, crippled aunt and a carnal uncle who lights his own farts. Few films boast as many indelible supporting characters equally Fanny and Alexander.

Bergman diehards ordinarily cite this as the director's most user-friendly pic, as though that's somehow a bad thing. Truthful, information technology contains more than in the way of light and warmth than some of his more than nakedly anguished masterworks. But light does not necessarily hateful light, and certain sections are as harrowing and profound as anything you find in Cries and Whispers or Through a Drinking glass Darkly. In fact, by the fourth dimension this flick pitches towards that amazing climax (bedsheets burning; magic working) one might even make a example for Fanny and Alexander every bit Bergman's well-nigh mature, clear-sighted and fully realised work.

It strikes me that the manager spent the bulk of his career tackling the notion of a world without God (how liberating this is; how terrifying, besides), only to get in at the conclusion that we are all God, and that man makes God in his ain prototype, for better or worse. Significantly, the God who crops upward in these final moments is represented by a cheap dummy, jiggled into life by an untrustworthy boob-master. He is also embodied by an overimaginative kid, still smarting from his father's death and sending malign thoughts out into the ether. Then he is, by implication, the director himself; a man who spent a lifetime conjuring entire worlds on a blackness-and-white screen and yet who never managed one equally beguiling, as terrible and true as the one nosotros run into here. Xan Brooks

vii. Days of Heaven

Art for art'southward sake, and proud of it, Days of Heaven has no reason to exist beyond the fact that Terence Malick was determined to get in exist and, every bit with all Malick's movies, it finally came to exist entirely on his own terms.

Using a story every bit wispy as a legend, Malick constructed 1 of the most mesmerisingly beautiful evocations of the past ever laid on celluloid. Set betwixt 1916 and 1918, it follows three urban fugitives (Richard Gere, Brooke Adams and Malick's wonderful discovery Linda Manz) equally they flee smoky Chicago for the Texas panhandle and seasonal jobs as wheat harvesters.

Days of Heaven takes time to linger on every exquisite image conjured up by Malick and his cinematographer, Néstor Almendros. A train loaded with harvest migrants sailing, it seems, over a high viaduct span; a locust storm that turns into a wheat-field inferno; the many harvest scenes shot at "the magic hour" later the sunday has gone down and its terminal horizontal rays remain.

Malick was adamant to emulate the silent movies of the movie's own historic setting, and therefore used many of the same methods, ordering his crew to plow off the lighting gear up-ups and allowing Almendros (and his replacement, Haskell Wexler) to use flick stock that greedily drank up the meagre low-cal available in the most gorgeously grainy ways.

The interiors are non studio-shot, but take place inside the edifice whose exteriors one sees in the movie. Against such beauty the humans inevitably seem similar small figures dwarfed by malign fate. But the performances are vividly existent and Manz'southward narration is i of the universal benchmarks of the movie voiceover. John Patterson

6. A Clockwork Orange

Even though it was fabricated in long-ago 1971, there is however something fetishistically futuristic about A Clockwork Orange. Perhaps that is owed to the exuberant and indelible production design, its characters' peculiar teenage argot ("nadsat") or its electrified, classical score by transsexual composer Walter (afterwards Wendy) Carlos – or maybe merely considering the early 70s were crazier – in hyper-stylised design and style – than any period since. Either way, A Clockwork Orange endures, not and so much for its philosophical musings on the nature of free will in the face of good and evil, but considering it is but a triumph of style from its opening sequence in the Korova Milk Bar through its cartoony violence and horrible retribution, all the way to its bizarre concluding shot of Alex (Malcolm McDowell in a function that has dogged him for 40 years) having wild sexual practice before an audition of voyeurs clad in Louis XIV courtier finery as he crows: "I was cured all correct!"

Kubrick idea of every detail in the costuming (the droogs' white thug outfits, with their crotch-emphatic outer jockstraps and bowler hats, not to mention Alex'southward false eyelashes), article of furniture, decor and art (the behemothic plaster penis that Alex uses as a murder weapon) – giving them as much attention equally he had to the dashboards of his bomber in Dr Strangelove, the spaceships in 2001, or the painterly compositions in Barry Lyndon.

Within the universe he created, he let loose a bandage of characters closer to grotesque gargoyle condition than anything in the remainder of Kubrick'southward body of work, and information technology is here that Kubrick outset deploys his tactic of starting close-up on a face up and pulling back drastically to show its surround (by the time of The Shining, about of his photographic camera movements tracked maniacally forwards, not sombrely backwards).

These days nosotros have crusade to wonder what all the fuss over the violence in the movie was about. It seems so tame at present (and probably did fifty-fifty and then, aslope, say, Straw Dogs). Plainly the copycat attribute of the audition response – certain fierce crimes were rumoured to have been inspired past the picture show – was real enough for Kubrick, who made the moving-picture show unavailable in his adopted homeland for the rest of his life. More's the pity, because it's a crucial British film of its menstruation, and a key to our larger understanding of Kubrick himself. JP

5. Citizen Kane

So many things about Citizen Kane were outrageous at the time: that this arrogant kid, Orson Welles, in his early on 20s, had a bargain to exercise what he liked; that he chose to make a thinly disguised lampoon of one of the most powerful men in the country, William Randolph Hearst; that it was a film ultimately near his ain flawed celebrity ("There, just for the grace of God, goes God," people said); that he made the picture show expect and sound richer, denser and more beautiful than anyone had dared before; that he took the mental attitude, "Don't await to empathise this on one viewing"; that he cared more most being outrageous than he did about the money.

If only a few of those ideas gained ground, Hollywood was in trouble. The secret might go out that moving-picture show could exist fine art! This astonishing, un-American notion took time to go established. The Hearst media did all they could to cake the film. Citizen Kane was a hard film for audiences raised on the slick narrative arc of Hollywood pictures to understand, with its scheme of flashbacks. And Welles would prove not just cocky-destructive, but also his own worst enemy – why let anyone else fill that vital job?

Yet information technology worked in the stop. Ordinary moving-picture show-makers knew that the work with lenses, darkness, audio and structure was unique. The film was total of wonderful new actors. The French critics seized upon it. By the late 50s, Denizen Kane was proverbial: it was cinema itself, a tribute to directors, also as the ability and opportunity of cinema. It breathed the unAmerican gospel: meet what one homo can do, run across how films can exist endemic and authored not by the factory, just past brilliant minds bent on self-expression.

And so a new orthodoxy gear up in, whereby Kane became the best movie ever made, a position it has held for 60 years. That greatness now hangs over the history and the futurity of the medium. Notwithstanding, if you lot have never seen it, prepare for one of the corking experiences in your life and observe this – Kane has lasted non for innovation lone, but because it is so emotional and tragic. It's a great human being asking himself whether anything matters. In Kane and Welles akin, there was the aforementioned rueful mixture of genius and lack of self-belief. David Thomson

iv. Tokyo Story

It's dangerous to start watching Japanese cinema, because the world is then extensive and dazzling you may chop-chop develop a sense of taste for zilch but Japanese films. Is there a romance more mysterious than Mizoguchi's Ugetsu Monogatari? Is there action to surpass Kurosawa'south Seven Samurai? And, in terms of family drama, has any flick been more than moving than Yasujiro Ozu's Tokyo Story?

Fourth dimension and once more, Ozu has made films nearly family, and the shifting structure we refer to equally "time and again". Family is less a fixed entity than a kind of weather system that keeps coming back. So children demand parents, and need to outlive them. Merely while the weather volition continue, and your children volition become parents, so your life will close, and you will not be there to encounter the way your own children look back as if to say they understand yous, besides belatedly.

Is this tragedy or comedy? Ozu is never quite sure. He seems to wonder whether whatever progression can corporeality to tragedy, or whether it is not but as inevitable every bit passing fourth dimension and irresolute calorie-free.

This may not audio "entertaining" or agile or even interesting, which only means the viewer needs to undergo the gentle process of beingness helped to meet through Ozu'southward withdrawn simply compassionate mode. So he watches from the corner of a room at a low level (for Japanese domestic life is often conducted from a sitting position) and he declines to rush in with forgiving, approving, loving close-ups – because he believes people are beyond forgiveness or individual glamour.

Family is a group in which anybody has his or her reason. In Tokyo Story, Shukishi and Tomi Hirayama (Chishu Ryu and Chieko Higashiyama) visit their grown children, full of hope and the wish to exist recognised, but they find the children too busy, too preoccupied. This is not depicted as bad behaviour, or a sign of cultural breakup; information technology is the style of the earth. The acting is intimate, humane and reserved yet there are no stars, permit alone heroes or heroines. There are no "happy endings" in the terms western civilisation requires. Instead, the riddle of happiness or its opposite runs through "fourth dimension and over again" similar lite on moving water. Does it sound ho-hum, or too simple? Exist warned – it tin can make other films seem unbearably crass. DT

three. L'Atalante

At the age of 29, Jean Vigo died from rheumatic septicaemia, simply a few days after the opening of his simply feature motion picture, L'Atalante. Those blank facts are a landmark not just in French cinema, but in the larger history of artistic film-making, and of the accented commitment of pic-makers. Moreover, the poetic lyricism of L'Atalante, far from dating, has been more appreciated over the years. 50'Atalante is 75 years old, notwithstanding its beauty and its harshness are yet hauntingly alive.

Three men work a barge (it is named L'Atalante) on the waterways of northern France: Jean, the skipper is young and hopeful (Jean Dasté); le père Jules, a tattooed veteran of the world's oceans (Michel Simon) and a motel boy. They finish at a small-scale town. Jean meets a daughter, Juliette (Dita Parlo), and they are married, while inappreciably knowing each other. And so the barge moves on. Information technology is not an piece of cake transition for the married couple. In Paris they go ashore and the wife flirts with some other man. There is a fight and she runs away, then the husband goes in search of her. Marriage is the film's bailiwick and information technology is most moving in its cinematic grasp of a deeper bond than that permitted by the lovers' temporary misalliance.

The simplicity of the story resembles silent movie theatre, but these people talk. The pic is enhanced past 1 of the cinema's offset neat musical scores (by Maurice Jaubert), and Vigo's inspired compositions and images in which the spirit of romanticism seems threatened by the very low-cal that reveals it. Only it's Boris Kaufman'south cinematography that is most impressive – it serves as an example of the way realism can exist infected past the characteristics of poetry and dream. Not the to the lowest degree legacy left by Vigo – to Truffaut and Godard, for example – was the essential artistic value of black-and-white photography and its curious simply hands forgotten establishment of a new way of seeing. DT

2. Mulholland Drive

Non many films accept managed to accept their block and eat it quite like Mulholland Drive (technically it's "Dr." not "Drive", which is important). It is a motion picture most the worst of Hollywood and the best; the dark, brutal undercurrents and the sparkly celebrity froth, the dream and the reality. But it's the style it twists the ii into some unfathomable Moebius strip that makes Mulholland Drive such a piece of work of art.

The film's greatest feat is to give u.s.a. all the thrills of a classic Hollywood film inside an avant-garde framework – and to become away with it. First-time viewers unfamiliar with Lynch's means volition be taken in by the initial ready-upwardly: an amnesiac automobile-crash victim (Laura Harring) staggers into the business firm of an aspiring actress recently arrived in town (Naomi Watts), but three-quarters of the way through, having been fatigued into a glossy noir fantasy, the rug is pulled out from under us completely. The aforementioned actors now appear to be completely different characters. The glamour has all evaporated. The relationships take all changed. Nothing'southward squeamish and sunny whatever more. Who's dreaming who? What goes where? What does information technology all hateful?

Piecing Mulholland Bulldoze together is half the picture's entreatment – and there's still no guarantee it all makes sense. Lynch fifty-fifty issued a fix of clues shortly after the release to guide people through the mystery – "observe appearances of the red lampshade" – which only made the story more cryptic. But even after nosotros retrieve we've deciphered it, the motion-picture show somehow loses none of its ability. That sense of being taken in, merely to realise we understood nada, gives us some emotional connection to Watts'southward character. And fifty-fifty as he's tying our brains in knots, Lynch is showing us behind the curtain in Mulholland Drive – showing us this is all really just his dream. Simply the illusions remain intact fifty-fifty after they've been dismantled. Lynch can still create charged scenes out of nothing simply a few skilled actors and our own subconscious. He knows how to push our buttons, and he shows us that he knows how to push button our buttons. And we dear it. Steve Rose

1. Andrei Rublev

Viewers and critics always have their personal favourites, but some films achieve a masterpiece status that becomes unanimously agreed upon – something that'southward undoubtedly true of Andrei Rublev, even though it'due south a film that people frequently feel they don't, or won't, get. It is 205 minutes long (in its fullest version), in Russian, and in black and white. Few characters are clearly identified, little actually happens, and what does happen isn't necessarily in chronological order. Its subject field is a 15th-century icon painter and national hero, notwithstanding we never run across him paint, nor does he do annihilation heroic. In many of the film's episodes, he is not nowadays at all, and in the latter stages, he takes a vow of silence. But in a sense, there is null to "become" virtually Andrei Rublev. It is non a moving-picture show that needs to be processed or even understood, only experienced and wondered at.

From the start scene, following the flying of a rudimentary hot air balloon, we're whisked away by silken photographic camera moves and stark compositions to a fourth dimension and identify where we're no less confused, amazed or terrified than Rublev himself. For the next three hours, nosotros're downwardly in the muck and chaos of medieval Russia, carried along on the tide of history through gruesome Tartar raids, bizarre infidel rituals, famine, torture and physical hardship. Nosotros experience life on every scale, from raindrops falling on a river to armies ransacking a town, often inside the same, unbroken shot.

With Andrei Rublev, Tarkovsky was consciously crafting a language that owed nothing to literature, and it's a pity so few others followed him. In today's picture palace, we're even so served up linear, crusade-and-event biographies of artists every bit if, past doing so, we'll understand the person and exist able to make sense of their art. Andrei Rublev operates according to a different understanding of time and history. It asks questions about the relationship between the artist, their society and their spiritual beliefs and doesn't seek to respond them. "In cinema it is necessary not to explicate, simply to act upon the viewer's feelings, and the emotion which is awoken is what provokes thought," wrote Tarkovsky in 1962.

Despite its apparent formlessness, Andrei Rublev is precisely structured and entirely aesthetically coherent. Acts of creation are mirrored by acts of devastation, at that place are themes of flying, of vision, of presence and absence; the more yous look, the more than you encounter. And then there are the horses, Tarkovsky'due south perennial favourite: horses rolling over, horses charging into battle, swimming in the river, falling down stairs, dragging men out of churches. At times the screen resembles a vast Brueghel painting come to life, or a medieval tapestry unrolling. We're always witting of life spilling out beyond the frame, and never conscious of the fact that this was made in 60s USSR. In Tarkovsky'south own turbulent fourth dimension, the film lit all manner of controversy. Its Christian spiritualism offended the Soviet authorities; its delineation of Russia's barbarous history upset nationalists like Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, and its challenging form led to various cuts. After opening in Moscow in 1966, it was suppressed until the 1969 Cannes film festival, and didn't attain Uk till 1973.

We don't necessarily know, or need to know, how Andrei Rublev works or what it's telling united states of america, but by the stop we're in no doubt it's succeeded. When in the final minutes, the pic pulls off its most famous flourish: the screen bursts into colour and we're finally ready to encounter Rublev's paintings in extreme close-up – coming at the cease of this epic journeying, they can reduce a viewer to tears. As the camera pores over the details, the tiny jewels on the hem of a robe, the lines forming a pitiful expression on the confront of an angel, the tarnished gilding of a halo, nosotros feel like we understand everything that's gone into every brushstroke. Nosotros're reminded of what beauty is. It is as close to transcendence every bit cinema gets. SR

0 Response to "Pretentious and Elitist About Tastes in Movies Music Art"

Publicar un comentario